Difference between revisions of "Early Wheel Development"

JohnNorris (talk | contribs) m |

JohnNorris (talk | contribs) |

||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| − | + | Development | |

Change ringers take for granted the full wheel they use today and assume that a full wheel is needed for full circle ringing. This is not the case and a little sketching with pencil and paper or a look at the sole of a bell wheel will show that a quarter of the wheel is not used by the rope. A three-quarter wheel is all that is needed. It is in fact possible to ring full circle with a 'half' wheel – actually a 5/8 wheel, extending approx. 225° from the vertical round to just beyond the bell mouth – and it is likely that this was the form of wheel in use for much of the late sixteenth and early seventeenth century. | Change ringers take for granted the full wheel they use today and assume that a full wheel is needed for full circle ringing. This is not the case and a little sketching with pencil and paper or a look at the sole of a bell wheel will show that a quarter of the wheel is not used by the rope. A three-quarter wheel is all that is needed. It is in fact possible to ring full circle with a 'half' wheel – actually a 5/8 wheel, extending approx. 225° from the vertical round to just beyond the bell mouth – and it is likely that this was the form of wheel in use for much of the late sixteenth and early seventeenth century. | ||

Revision as of 23:14, 1 December 2009

Development

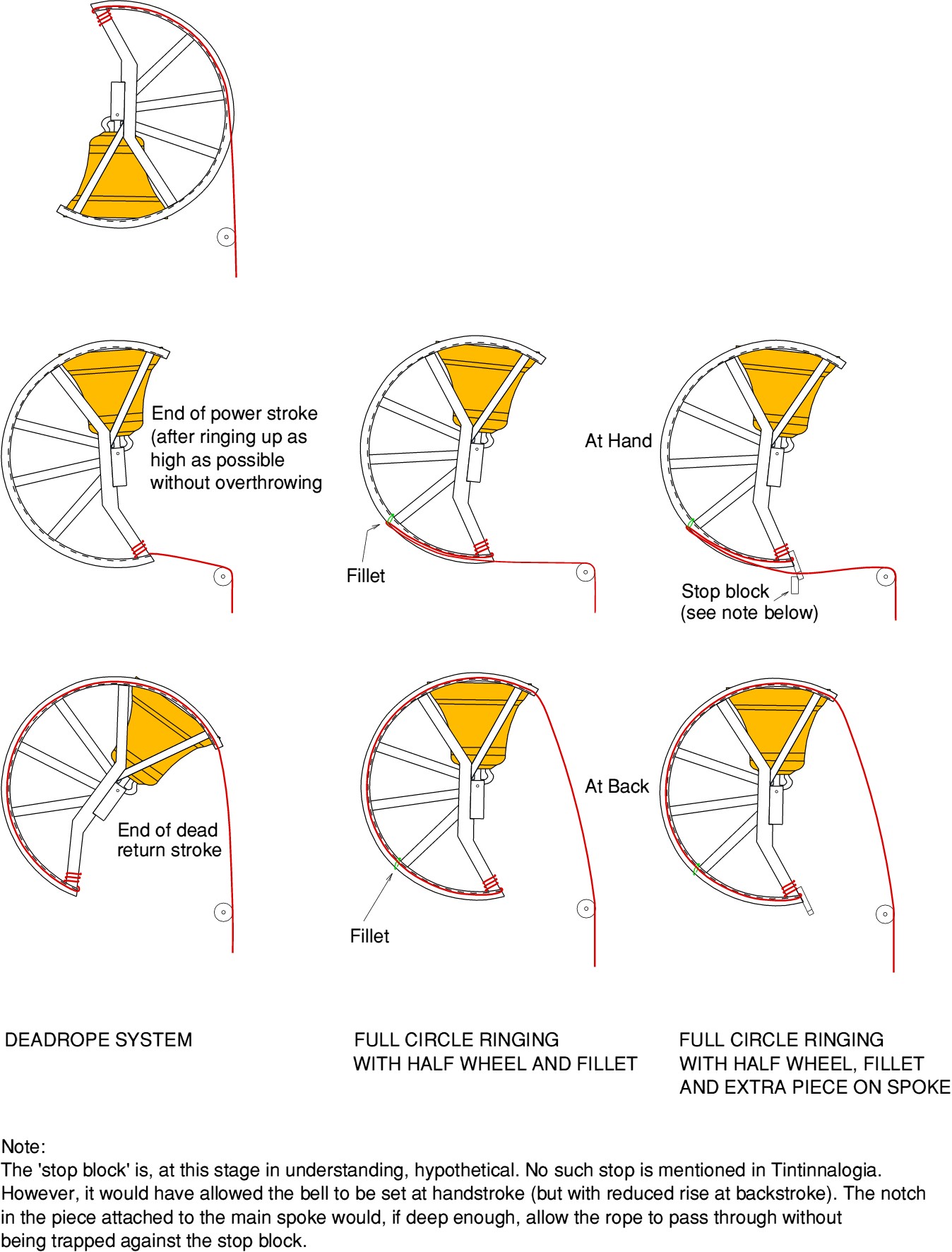

Change ringers take for granted the full wheel they use today and assume that a full wheel is needed for full circle ringing. This is not the case and a little sketching with pencil and paper or a look at the sole of a bell wheel will show that a quarter of the wheel is not used by the rope. A three-quarter wheel is all that is needed. It is in fact possible to ring full circle with a 'half' wheel – actually a 5/8 wheel, extending approx. 225° from the vertical round to just beyond the bell mouth – and it is likely that this was the form of wheel in use for much of the late sixteenth and early seventeenth century.

However, at some point in this period, probably c.1600, and before the extension of the wheel to a full wheel, a development took place that transformed ringing. The memory of this development is perpetuated today in the name 'garter hole' or 'fillet hole' for the hole in the sole of a modern wheel through which the end of the rope passes on its way to its attachment to the vertical spokes – even though a garter is nowhere to be seen!

Whether by careful thought or happy chance it was discovered that if the rope was trapped to the wheel at the point where the garter hole is today, a useful return stroke would be produced – what today is termed the handstroke. Prior to this it was only possible to pull the rope on the 'outward' swing of the bell, leaving it to swing back unassisted. With this 'dead-rope' system it was possible to ring a bell up to the balance and even 'overthrow' it but control was limited. The effect was rather like ringing a modern bell up without touching the sally. It seems likely, if not certain, that Rounds could be, and were, rung in this way. There is also evidence that other orders such as Queens and the back change (ringing up the scale to warn of fire) were recognised and rung in late Elizabethan times. However, it isn't known whether these different orders were rung from a 'standing start' or were reached by progressive changes from Rounds.

The trapping of the rope to produce a handstroke was at first achieved by a 'fillet' – a little cord or garter – tied around the rim of the wheel. This is alluded to in Tintinnalogia.(1668) where is written:-

"If a Bell have a longer stroke on the one side, than the other, truss up that side which hath the short stroke more, or let the other side down, and put a piece or two of Leather in, according to the stroke; but sometimes the fault of the stroke is in the Sally, which you may remedy, by tying the Fillet (or little Cord about the rim of the Wheel, which causeth the dancing of the Rope) nearer, or farther off the main Spoke; nearer makes a short stroke, farther off the Spoke, a long one."

Wheel Diagrams

What is much more puzzling is the statement in Tintinnalogia that:-

“ ’Tis very convenient (if the Frame will permit) to fasten a piece of Timber about half a foot long on the end of the main Spoke at the top of the Wheel (whereon the end of the bell-rope is fastened) with a notch on the end of it; so at the setting of the bell, the Rope will hit into that notch from the Rowle, and this will make the bell lie easier at hand when it is set, and flie better.”

It has been assumed by some that this piece of wood attached to the main spoke was intended to act as some sort of stay but this seems difficult to believe, for several reasons:-

- No mention is made of any stop block for it to rest against.

- If used as a setting device it would have been potentially very injurious to the wheel.

- The slot in the wood necessary to allow the rope to pass through it clear of contact with a stop block would have been so long as to render the term 'notch' inappropriate.

The more plausible alternative, as suggested by John Eisel in Change Ringing, The History of an English Art(p.57) is that the piece of timber was apparently:-

"designed more to control the rope at handstroke and prevent it slipping wheel than to set the bell."

However, it isn't easy to see quite how it would achieve this. Certainly it would cause a little more rope to be drawn up at handstroke, but only a few inches and arguably hardly enough to be significant.

Sources:

Change Ringing, The History of an English Art, Gen.Ed. J. Sanderson, CCCBR 1987.

The History and Art of Change Ringing, Ernest Morris, 1931.

Contributions by ringers to the Change Ringers email list in November 2009 on the subject of 'early fittings'.